In todays digital and multi connected age, cyberattacks are more frequent than ever before. Constant growth of online services and activities offer continuous business opportunities and advantages, thus profits to be made. Growth and profits attract attention, and the intentions of some of those looking are not always benevolent. Either because of hacktivism, cyber vandalism, extortion, competition or cyber warfare, online services get attacked and brought down daily with DDoS (Distributed-Denial-of-Service) being the most frequently used method. Flooding network infrastructure with the main goal of rendering online content and services unavailable has been around for a while and we bring you a chronological list of the 15 most notorious and dangerous DDoS events to ever hit the e-universe.

1. The Morris worm

Considering the nature of DDoS attacks, the first ever documented event of that type dates back to 1988 when Robert Morris wrote a self-replicating computer program, which later on had a significant influence on the Web. The malware was quickly detected during the spreading due to its large consumption of system resources. Although Morris did not launch attacks by controlling infected computers in a centralised way, it was the rudiment of DDoS attacks by exploiting botnets. Injecting a Trojan virus by exploiting system vulnerabilities and launching attacks against the target through botnets are the most common technical methods of DDoS attacks.

How One AI-Driven Media Platform Cut EBS Costs for AWS ASGs by 48%

2. Panix – SYN Flood and domain hijacking (1996 and 2005)

One of the first known and publicly documented DDoS attacks. It was launched in September, 1996 (although documentations vary) against Panix, New York City’s oldest Internet service provider. The attack targeted different computers on the provider’s network, including mail, news, name and Web servers along with user “login” machines. A SYN flood was used to exhaust available network connections and prevent legitimate users to connect to Panix servers. It took about 36 hours of frantic work by a globe-spanning group of Internet specialists to finally regain control of the Panix domains. In 2005, the “panix.com” domain name was hijacked again over a US long holiday weekend. It wrecked havoc for customers and Panix staff worked around the clock over the weekend to recover services after the rug was pulled out from under its business.

3. Electronic Disturbance Theater – FloodNet (1990´s)

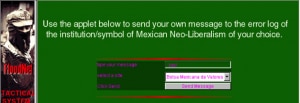

The next major milestone was the use of DDoS by the Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT), an electronic company of cyber activists, critical theorists, and performance artists. Originating in the 90s, and attracting the attention of the media by the end of the decade, the hacktivist group described DDoS as akin to a “virtual sit-in.” One thing that separated them from their predecessors was the use of in-house developed tools, which allowed anyone outside of the organisation to join in. Their kit, called FloodNet would simply reload a URL for short several times; effectively slowing the website and network server down if a high number of protesters were to join in at one time. The EDT would first execute the FloodNet software in what would be for them a dress rehearsal before attacking their main targets, both Mexican and American government websites representing the Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo and American President Bill Clinton. Those wishing to join the “sit-in” simply selected their target from a drop down menu, clicked attack, and waited while FloodNet automatically bombarded the offending server.

4. Estonian cyberattacks (2007)

In April 2007, a series of DDoS attacks swamped Estonian organisations websites, including those of the Estonian parliament, banks, ministries, newspapers and broadcasters. The cyber attacks escalated after the Estonian government decided to relocate the Bronze Warrior, a Soviet World War II memorial statue located in Tallinn, to a military graveyard. Most of the attacks that had any influence on the general public were DDoS attacks ranging from single individuals using various methods like ping floods to expensive rentals of botnets.

Although the headlines at the time announced it as the first “cyber war”, it was later declared as hacktivism with no evidence of direct correlation to official Moscow.

5. Anonymous vs the Church of Scientology (2008)

In 2008 Anonymous launched a DDoS siege against the Church of Scientology. It was a response to the church’s attempt to remove the highly-publicised interview of Tom Cruise, a prominent member of the church, from the Internet in January 2008.

The attack started with a YouTube “Message to Scientology” on January 21, 2008 and was followed by a massive raid of DDoS, prank calls, black faxes and other disruptive methods. What was known as Project Chanology began to attract mainstream attention and eventually turned up as the biggest protest movement against the Church of Scientology. This was the result (seen on scientology.org):

6. Massive botnet invasions (2009)

In July 2009, a series of coordinated cyber attacks occurred against major government, financial websites and news agencies of both the United States and South Korea that involved the activation of botnets. The numbers of hijacked computers varied depending on the sources and included 50,000 from the Symantec’s Security Technology Response Group, 20,000 from the National Intelligence Service of South Korea, and more than 166,000 from Vietnamese computer security researchers as they analysed the two servers used by the invaders.

In a three wave series of attacks the botnets affected Pentagon, White House, US State Department, National Intelligence Service of South Korea websites and many others. The perpetrators were never identified.

7. Wikileaks hacktivism (2010)

In December 2010, the document archive website WikiLeaks, used by whistleblowers, came under intense pressure to stop publishing secret United States diplomatic documents. In response, Anonymous announced its support for WikiLeaks and launched DDoS attacks against Amazon, PayPal, MasterCard, Visa and the Swiss bank PostFinance, as retaliation acts for perceived anti-WikiLeaks behaviour. The second front in the December offensive was performed under the codename Operation Avenge Assange. Due to the attacks, both MasterCard and Visa’s websites were brought down on December 8. A threat researcher at PandaLabs said Anonymous also launched an attack which brought down the Swedish prosecutor’s website when WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was arrested in London and refused bail in relation to extradition to Sweden

8. Arab Spring cyber warfare (2011)

While mainstream media was slow to tune in to the revolutionary drumbeat that has been rising in the Arab world, Anonymous was present from the beginning. In 2011 the websites of the government of Tunisia were targeted by Anonymous due to censorship of the WikiLeaks documents and the Tunisian Revolution. The group took down at least eight government websites with DDoS attacks beginning on January 2. The Tunisian government responded by making its websites inaccessible from outside Tunisia. Tunisian police also arrested online activists and bloggers within the country and questioned them on the attacks. Anonymous quickly created a “care packet”, translated into Arabic and French, offering cyber dissidents advice on how to conceal their identities on the web, in order to avoid detection by the regime’s cyber police.

They also developed a “greasemonkey” script – an extension for the Mozilla Firefox web browser – to help Tunisians evade an extensive phishing campaign carried out by the government.

Following up in 2011, during the Egyptian revolution and as a reflection of the mood on the streets of Cairo, it was decided by the hackers not to attack media or to promote violence. Egyptian government websites, along with the website of the ruling National Democratic Party, were hacked into and taken offline by Anonymous. The sites remained offline until President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. The hacktivists also released the names and passwords of the email addresses of Middle Eastern governmental officials, in support of the Arab Spring. Officials from Bahrain, Jordan, Libya and Morocco were also targeted.

9. LulzSec vs HBGary Federal (2011)

On the weekend of February 5–6, 2011, Anonymous had successfully infiltrated the sites of HBGary Federal, the US security firm. Aaron Barr, the chief executive, stated earlier that he could exploit social media to gather information about hackers.

It took a handful of hackers less that 24 hours to take complete control over the HBGary Federal website and databases. They also seized Barr’s Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo and even his World of Warcraft account. They replaced the HBGary Federal homepage with this declaration. At the same time, they were able to use social engineering techniques to SSH into the rootkit.com site and delete its entire contents.

Using a variety of techniques, including social engineering and SQL injection, Anonymous went on to take control of the company’s e-mail, dumping 68,000 e-mails from the system, erasing files, and taking down their phone system. The leaked emails revealed the reports and company presentations of other companies in computer security such as Endgame systems who promise high quality offensive software, advertising subscriptions for access to “0day exploits”. Among the documents exposed was a PowerPoint presentation entitled “The Wikileaks Threat”, put together by HBGary Federal along with two other data intelligence firms for Bank of America in December. The Anonymous group responsible for these attacks would go on to become the elite hacking team known as LulzSec.

10. Operation Megaupload (2012)

In January 19th, 2012, 500-million user file-hosting service Megaupload was seized and shut down by the U.S. Department of Justice and indicted its executives on numerous charges, including criminal copyright infringement and conspiracy to commit money laundering. According to the indictment, the defendants generated $150 million in subscription fees overall and $25 million in advertising over the course of five years. It also alleges that Megaupload founder Kim Schmitz (alias Kim Dotcom) made more than $42 million in personal income in 2010 alone.

As a response, Anonymous DDoSed the websites of UMG, the company responsible for the lawsuit against Megaupload as well as websites of US Department of Justice, US Copyright Office, FBI, MPAA, Warner Bros and HADOPI, all in one afternoon. On the day of launch, 10 high-profile government and music industry websites were reportedly brought down. By midnight on January 20th, AnonOps declared the operation a success with over 5,635 people using Low Orbit Ion Cannon to bring down the targeted sites.

11. Chinese internet breakdown (2013)

In 2013, part of the Chinese Internet went down in what the government entitled it as the largest DDoS attack it has ever faced. According to the China Internet Network Information Center, the attack began at 2 a.m. Sunday morning and was followed by an even more intense attack at 4 a.m. The attack was aimed at the registry that allows users to access sites with the extension “.cn”. It resulted in the domain consistently slowed and blocked Internet access accessibility for hours. China has one of the most sophisticated filtering systems in the world so significant damage was avoided.

12. Cyber Fighters of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam vs U.S. banks (2013)

Again in 2013, an Iranian hacking collective — Cyber Fighters of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam — has claimed credit for orchestrating sophisticated attacks that have overwhelmed the expensive security systems U.S. banks have put into place to keep their online banking services up and secure. The first wave of DDoS attacks attributed to the Cyber Fighters of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam began in September 2013 and lasted about six weeks. Knocked offline for various periods of time were Wells Fargo, U.S. Bancorp, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and PNC Bank. The second wave commenced in December and lasted seven weeks, knocking out mid-tier banks and credit unions. And a third wave of high-powered DDoS attacks commenced in March targeting credit card companies and financial brokerages. The attacks were a continuation of the Operation Ababil that originated in 2012. The operation used JS LOIC malware similar to Anonymous´ and was put into force as a revenge act for an anti-Islam film that was uploaded to the Internet and, as stated by the group, insulted the prophet of Islam, Muhammed.

13. Lizard Squad vs PlayStation & Xbox (2015)

A black hat hacker group named Lizard Squad started disrupting online gaming services during 2015 with the purpose of, as they stated, raising internet security awareness and for simple amusement. Large DDoS attacks were launched against the websites of Xbox Live and PlayStation Network. Curiously, the attacks were announced weeks earlier. Lizard Squad member Ryan stated “”They should have more than enough funding to protect against these kind of attacks.”

The group also conducted a marketing campaign for promoting their DDoS tool, known as the Lizard Stresser, using which the group took down Sony’s PlayStation Network and Microsoft’s Xbox Live services again in the year 2015, on Christmas Eve.

14. Greatfire.org – DDoS and DNS poisoning (2015)

In 2015, Chinese activist site Greatfire.org which masks censored traffic into the country was under a sustained distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack that racked up to $30,000 a day in server costs. The attackers were trying to DDoS the website into bankruptcy. Website admin Charlie Smith reported that the attack was delivering 2.6 billion requests an hour, about 2,500 times more than normal levels. GreatFire alleged the attacks to be the handiwork of Beijing. The Cyberspace Administration of China labelled GreatFire a foreign “anti-China website”. In November the same year, the activists said authorities also used DNS poisoning against its content delivery network EdgeCast which caused mass outages and service interruptions.

15. New World Hacking vs BBC & Donald Trump (2016)

Most recently, in January 2016, the so-called New World Hacking group claimed responsibility for taking down both the BBC’s global website and Donald Trump‘s website. The group targeted all BBC sites, including its iPlayer on-demand service, and took them down for at least three hours on New Year’s Eve. The attack was initially described as the largest one in history, and it allegedly measured over 600 Gbps which was never proven.

The group likely used a tool called Bangstresser – apparently contradicting claims that they developed their own web interface. The Bangstresser tool could theoretically buy enough firepower to conduct an attack at a size of more than 400 Gbps with a so-called “layer 4” attack.

The BBC’s website returned after about three hours, but it would’ve taken longer without help. The service was restored to the new, non-legacy portion of its website with help from Akamai’s content delivery network. By moving the attacked block of internet addresses the service was mostly back to health by the afternoon.

As the list flow suggests, cyber attacks are increasingly sophisticated and of enormous magnitudes. A Q1 2016 State of the Internet Security Report indicates that DDoS attack activity has risen to record levels involving a web application level attacks surge and a continuous rise of multi-vectored attacks making mitigation more difficult (56% of DDoS attacks in Q1). It also reports an increased trend of repeat DDoS attacks with an average of 29 attacks per targeted website – including one case who was targeted 283 times.

It’s fair to say that today executing a DDoS attack is easier than ever and everyone with some basic knowledge and the right motive can find a way to attack a website. Adequate security solutions have become of the utmost importance for any serious online endeavour. Ongoing evolution of the attacks complexity and damage has increased the demand for top-notch tailored security solutions which further fuelled a development race between both sides.

“If you spend more on coffee than on IT security, you will be hacked. What’s more, you deserve to be hacked.”

Richard Clarke – National Security Council (NSC)